Climate and Biodiversity

This site is under redevelopment. Its content is from 1998, but we will be updating it in the near future.

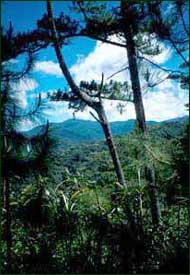

Temperature, on average, declines with increases in elevation. Baguio City, for example, often called the "summer capital of the Philippines," was chosen as a refuge from the summer heat of Manila because it lies 1,524 meters above sea level in the Central Cordillera. When air blows uphill, it gradually expands due to the slow decline in pressure (resulting from the reduced weight of the air above it in the atmosphere). As the air expands, it cools at a rate determined by its water content; air that is saturated with water cools more slowly than dry air. In the Philippines, where air is almost always humid, it cools at an average rate of 6° Centigrade for every 1,000 meters that it rises. On a hot, muggy day in Manila, when the temperature is a sizzling 34° C (93° Fahrenheit), it will typically be 25° C (77° F) in Baguio. Still higher in the mountains—for example, near the top of Mount Pulog, northof Baguio at nearly 3,000 meters elevation—the temperature would typically be only 16°C (61° F).

Along with the change in temperature comes a change in precipitation. As air cools, it gradually loses its ability to hold humidity; when it reaches its saturation point, water molecules begin to gather in tiny droplets and form clouds. Clouds often produce rain, but they also become fog when they encounter the top of a mountain. As a result, rainfall (and dew-fall) usually increases as we go up any given mountain. The lowlands of the Philippines experience roughly two meters of rain annually, but at 900 meters elevation (about 3,000 feet), rainfall is approximately two and a half times higher. Farther up in the mountains, at about 2,000 meters elevation, rainfall is often five times higher than in the adjacent lowlands.

The net result of these changes in temperature and precipitation is dramatic. While daytime temperatures average 30°C in the lowlands, they rarely exceed 18°C on the mountains 2,000 metersabove sea level, and while the lowlands receive two meters of rain annually (about six feet, a bit more than twice the yearly average of Chicago), the mountains may be subject to as much as 12 meters per year (about 40 feet). Lowland rain forest is wet, but mossy forest in the higher mountains is much, much wetter.

Another feature of the Philippine climate is one that every citizen of the country knows only too well: The Philippines lies at the center of the primary typhoon track in Asia. As many as 33 typhoons can strike the archipelago in a single year, with 15 to 25 being typical. These storms bring winds powerful enough to topple high-tension power lines and tear bamboo huts to shreds, and can drop half-a-meter of rain or more in a day.

When such heavy rain falls on rain forest, the leaves of the trees break its fall so that it lands softly on the ground, which is usually loosely covered with leaves and small plants. In high-elevation mossy forest, where rainfall is still heavier and the terrain much steeper, thecool temperatures allow the accumulation of thick layers of partially decomposed leaves, branches, and moss which function as a huge sponge. A meter of rainfall in a day in mossy forest produces remarkably little flooding; most of the moisture simply disappears into the natural sponge of humus and soil, to be gradually released from springs in the lowlands.

|